Hounds of the Middle Age

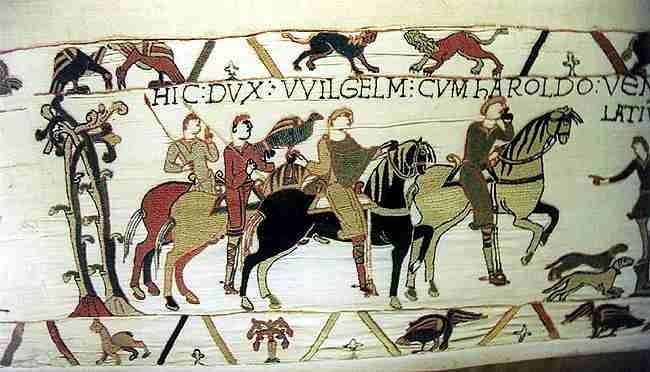

The history of the medieval dogs is connected with the hunting practises of those days. Princely hunters on horseback leading a pack of hounds and binding the inhabitants of whole villages to act as beaters. That used to be the way of hunting wild boar, bear and wolf which could be found in large quantity in the extensive forests of Central Europe. It was the time Riedinger and van Dyck made us aware of with their marvellous pictures. First accounts about these hounds can be found in the descriptions of the hunts of Landgrave Philipp the Magnanimous of Hesse, who was a very passionate hunter. The English dogs which are mentioned here, were tall and strong animals that have been bought from England by the princely courts of the continent at the beginning of the 16th century. They emerged from a cross-breed of a Mastiff and an Irish Greyhound. The kennel they were kept in was called the English Stable, whereas the dogs themselves were known as Male, Hounds, “Saufänger” or “Saupacker”. Johann Täntzer’s “Diana’s high and low secrets of hunting” (1699) provides a in-depth description of these big danelike dog breeds. In order to save these precious dogs from harm whilst the hunt, they were equipped with a special armour. According to Täntzer these ‘coats’ were made of brown parchen or some silk fabric, well padded and equipped with whalebone on the dog’s chest and stomach. Täntzer also reports that the ‘great masters’ chose only the most beautiful and biggest dogs of the pack to be the leader or his private dog. Those chosen ones wore silver and silver-golden collars that were upholstered with velvet and decorated with valuable fringes. The enormous distances during the hunts of Landgrave Philipp and William IV in the forests of ‘Habichtswald, Reinhardswald and Kaufunger Wald’ show the capability of these hounds of the Middle Age.

In 1559 Landgrave Philipp sent the following message to Duke Christoph of Württemberg: “It is with great pleasure that we managed to hunt down more than 1,120 pigs with the help of our own dogs that we have raised ourselves.”

The perils the hunters were exposed to every now and then during the hunts can be gathered from a letter from Landgrave Philipp IV. There he mourns the death of his most upright squire, Claus Rantzau, who went in search of the pigs with a spike and was then killed by a wild boar that tear open the main vein of his left thigh. Naturally there was also a great loss of the hounds. “He who wants pig heads must give up dog heads.” as said a proverb in the old days. In the course of the 18th century the import of English dogs gradually stopped due to the fact that indigenously bred dogs were preferred. Another possible reason might be the lesser game population and the use of firearms which made a pack of dogs no longer necessary.

Only small numbers of hounds were still kept at the hunting courts in the princely provinces. At the beginning of the 19th century these dogs were continually passed into private ownership. In terms of the outward appearance of these medieval hounds, you can find the same coloration as our Great Danes have nowadays; according to written reports of ancient hunting authors. The original type, a yellow coloring, maintained in Hesse for the longest period. “Game Master Otto-Kassel, who belonged to the Hessian hunting court as a princely hunter from 1860 until 1870, was kind enough to give me some more details about the last of their phylum. According to him they have been vigorous dogs of a yellow, reddish-yellow, cloudy color, a black muzzle and for the most part they have been big and fast animals that have been used exclusively for hunting pigs.” (Göschel)

19th Century – A name becomes a meaning

There is hardly any other dog race that caused such a confusion: “Saupacker”, “Hatzrüden”, “Fanghunde”, Danish Dane, Ulmer Dane, Tiger Dane and Bismarck Dane were the names known for Danes in the middle of the 19th century. What we have here is, ancient names meet those of local breeding regions. Southern Germany, mainly Württemberg was famous for breeding black and white Harlequin Danes, which were called Ulmer Dane. Breeders of the Northern part of Germany preferred blue and fawn colors. The lay public still calls them Danish Danes even nowadays.

It is not totally clear yet why our Harlequins were called Tiger Dane. Maybe this name derives from those big Danes of this color that, as it is reported, were kept among tigers in zoological gardens or appeared in circus rings. It is also possible that the name derives from the dappled horses of the Indians, the Apaloosa. (tiger horse). In the middle of the 19th century Germany has been caught by the surge of dog sports from the UK. The first German dog show took place in Hamburg-Altona in 1863. Danes were also present; eight of them were registered as Danish Danes and seven as Ulmer Danes.

They judged likewise according to this differentiation at the subsequent shows in Hamburg (1869 and 1876) and Hanover (1879), even though a group of judges already explained in 1876 that it is impossible to keep up this differentiation, since they both belong to the same breed. Their suggestion was to unite all colors under one term: “Deutsche Dogge” (German Dane). The final decision for this however, was not until 1880 when during a convention of judges in Berlin, under the chairmanship of Dr Bodenius, the name “Deutsche Dogge” was established.

We can be proud that this name became a kynological ‘trademark’ and that Germany, of all member countries of the worldwide Fédération Cynologique International (FCI), is acknowledged to be the country of origin of this breed. But no rose without its thorns. In France and other Anglo-Saxon countries our Dane is still being called “Grand Danois” or “Great Dane”. It will probably remain a mystery forever why especially this name found its way. By the way, this name has literary been used for the first time by the French naturalist Buffon (1707-1788). There is, however, no hint for Denmark taking a big part in the creation or formation of this breed. I presume that political resentments led to a deviate naming. Possibly a reaction of our Western neighbours to the displayed German national consciousness of those days.

In 1870/ 71 the German-French war was won by Prussia and King William I of Prussia had been proclaimed German Emperor in the castle of Versailles. The founder of the first German Empire was the Imperial Chancellor Prince Otto von Bismarck, a man whose love was devoted to Danes since his early youth. So what was more reasonable than choosing the name “Deutsch” (German) for a big majestic breed and to declare the “Deutsche Dogge” national dog.